The Claim – Independent Scotland cannot afford to establish an independent civil service.

The Truth – Scotland already pays for most of the extra civil and public servants we would need but they are based in England and Wales, their taxes are not counted as Scottish and they do not benefit Scotland’s economy by spending money in Scotland.

Pro-Union politicians often claim that the costs of setting up a Scottish civil service would be prohibitive and that the Scottish Government would find it hard to hire skilled workers for new roles. Our research shows that the costs would definitely not be prohibitive and that framing the issue in this way ignores the huge economic positives of moving the civil service to Scotland.

In fact, the gains from creating or relocating additional civil and public services jobs, through tax revenues and new economic spending, will far outweigh any potential additional costs. There is also already significant layers of Government infrastructure in place to take on many of these functions. Creating an independent Scottish civil service is a significant opportunity for Scotland.

The costs and logistics of setting up an independent Scottish civil service

According to research undertaken by the London School of Economics, the total transition costs to establish an independent Scottish civil service would be £90 million per year for five years. These costs account for the transition period and the first three years after this, which is believed to be ample time to complete the reorganisation of the civil service.

The majority of UK government departments have some physical presence in Scotland. This means that across most policy areas there is scope for repurposing existing civil and public services infrastructure.

This is especially true after the extension of tax powers under the Scotland Act 2016. The Scottish Parliament has recently started to establish tax collecting bodies Revenue Scotland and the Scottish Social Security Agency which would be able to expand their remits to deliver the full range of services. All this would require is reorganisation at the managerial level, which would bring the benefit of a greater number of managerial-level positions.

This just leaves departments where there is minimal Scottish presence and entirely new organisations will need to be established. This is where the majority of the cost comes from. These are:

- defence and armed forces

- foreign ministry and diplomatic services

- integrated security and intelligence agency

- central bank and financial regulation

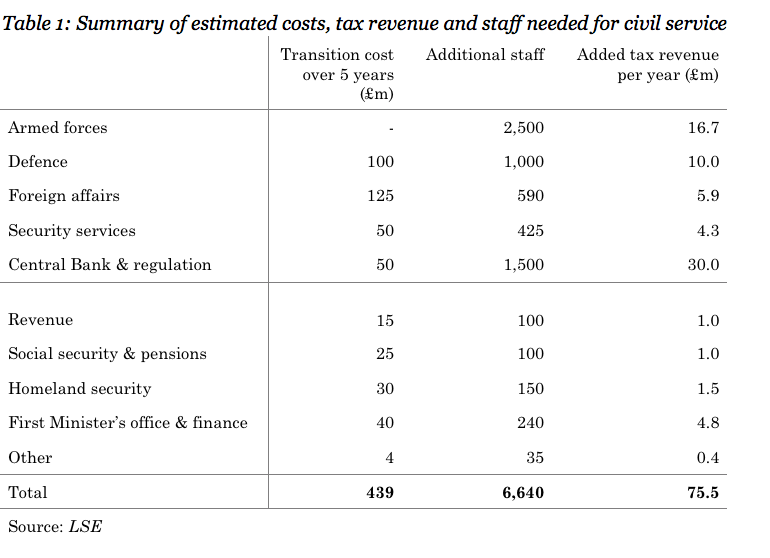

LSE’s projection is based on a weighted calculation for similar-sized countries. Table 1 summarises the costs over the five-year transition, the additional staff required, and the additional tax revenue gained.

These transition costs are not insignificant but they are also low enough to be easily absorbed within existing budgets owing to the likely reduced demand for spending on defence and foreign affairs due to policy changes. Furthermore, the £450 million in transitional costs would be recouped within six years from the added tax revenues, after which it would make a net contribution to the budget.

It is also key that money spent in Scotland brings more benefit to the Scottish economy.

Take defence as an example, which is set to cost £100 million. Currently, Scotland pays for 1,808 more military personnel than live in Scotland. This means despite our contributions to the UK’s defence budget we do not gain from it, as it is not spent in Scotland. This spending also does not reflect the preferences of the majority of Scottish people (for instance 58% of Scots are against renewing the UK’s nuclear weapons programme Trident). It is likely that Scotland’s defence remit will change considerably to be more in line with this. Spending will be more effective if decisions about what is spent are made by the people who live there.

It can also be argued that policy realignment will generate significant savings. As part of the UK, Scotland pays a population share of a defence budget that is based upon projecting power, as an independent nation Scotland has signalled a desire to protect peace.

It can also be argued that the consequential economic benefit to Scotland of representing itself on the world stage and having a distinct fiscal and monetary policy tailored to the needs of Scotland’s economy, would far outweigh any transition costs. However, this is beyond the scope of this article, which is focused on examining the short term costs/benefits.

Comparing to the cost of Brexit

The cost of Brexit to Scotland really highlights this. Even a soft Brexit is set to cost Scotland between £3-5 billion a year in Gross Domestic Product whilst lowering real average wages by £800-1,200 a year. Seeking independence within the EU is clearly the best option financially if all civil service transition costs can be offset many times over by avoiding the Brexit costs to Scotland.

Scotland already pays the wages of civil and public servants

Currently, the UK Government manages and pays the wages of civil servants who do work on Scotland’s behalf but are not based in Scotland. It does the same for civil servants who work in areas not devolved such as Department for Work and Pensions or the DVLA which is based entirely in Swansea. In both cases, the Scottish Government is billed a population percentage share of the costs and they are applied as a cost in Scotland’s accounts.

However, the tax and national insurance contributions of these people are applied to the accounts of where they live, not to the accounts of the Government that the costs of their wages and other employment costs are applied to. In other words, under the UK system, the Scottish Government pays the wages of civil servants but gets neither the tax National Insurance or economic benefit of having those jobs based in Scotland. We get financial pain but no economic gain.

This means that the cost of hiring civil servants remains roughly the same, probably lower as civil servants who work in London are paid more, but the revenues gained would go directly to the Scottish Government. This includes direct taxes, such as the income tax paid by civil servants, and indirect taxes on goods purchased such as VAT.

The potential for job gains

To be clear, 88% of Scotland’s public-sector staff work in areas that are already fully devolved. Most of these staff work in areas such as local government and the NHS. Absolutely nothing will change for these staff.

However, in those departments that deliver services across the UK but are located in one constituent nation, there is the question of what will happen to these staff. Will the UK be responsible for those staff or will they be relocated? Either way, it remains a fact that Scotland already pays a population share of their wages so this is not the issue.

During the last referendum, the UK press talked up hypothetical job losses in Scotland without giving consideration to the gains. The then Secretary for International Development Justine Greening told MPs that 600 jobs would be at risk at DfID in East Kilbride if Scotland were to vote for independence. Naturally, this caused concern and raised broader questions about how assets (staff included) should be divided following independence.

In the white paper on Scotland’s Future, the Government had said that civil service jobs would be guaranteed ‘either by transfer to the Scottish Government or through continued employment by the Westminster Government.’

The Growth Commission report has made more concrete reassurances. For staff in departments where services are only delivered to Scotland, there will likely be little change in circumstances. The SGC propose such staff will transfer across to the Scottish Government under ring-fencing arrangements, with some choosing to relocate or retire. This means that jobs in this field will be effectively safeguarded including the DWP functions, where 11% of total staff are employed in Scotland.

As for departments where services are delivered internationally or across the UK, this will be subject to a negotiation between the UK Government and the Scottish Government who will surely prioritise stability over political gain. An indication of the latter’s intentions could be seen during the last referendum where then Scottish International Development Minister Humza Yousaf pledged cooperation between the two departments in the interests of preserving jobs, even stating that he had ‘no aversion’ to DfID having a presence in Scotland post-independence.

Indeed, inter-departmental cooperation is likely across many different departments for at least the transition period if not further. It is possible that a mutually beneficial agreement could be reached for contracting services between the UK and Scottish departments. This would be in the interests of the rUK too, where there are even greater potential job losses from the repatriation of departments to Scotland. However, if Westminister were to be hostile to mutually beneficial cooperation then Scotland could establish the required departments quickly.

Improved career prospects for civil servants

Scotland would be more than able to deliver the same level of public services regardless of agreements with the UK. There are currently 543,000 public sector employees in Scotland. After independence, the additional staffing would increase public sector employment by 1% or 6,640 additional jobs.

As a report by the Institute for Government demonstrated in 2013, UK-wide department staff based in Scotland are drawn disproportionately from the lower grades, with only a few senior civil servants. For instance, the DWP has just 10 senior civil servants overseeing 10,000 operational and administrative staff.

This is precisely because of the London-centric government system that an independent Scotland seeks to escape from.

As can be seen in Table 1, the Scottish Government can cope with the costs easily. Scotland also has the most educated population in Europe, making it somewhat preposterous that they could not fill higher managerial positions.

The benefits of relocating the civil and public service to Scotland

The opportunity for advancement in the civil service should be seen as a net benefit to Scotland, and something which attracts people to the country and incentivises them to stay. Currently, many talented graduates wishing to join the civil service are forced to go to London.

From these additional jobs, there are direct benefits, such as the greater number of taxpayers. The LSE figures are based upon conservative estimates of the average wages in each of these fields (for instance the armed forces salary is based upon £20,000, the salary of a Private yet many are paid considerably more than this). Civil servants tend to make higher wages than the average and therefore pay a greater percentage of tax which would benefit the Scottish Government directly. Direct taxes alone would generate £75 million.

Not only this, these additional workers being paid higher wages will indirectly benefit the local economies where they are posted. This can be seen in the DfID complex in East Kilbride which has regenerated the area. Currently, civil servants administering Scottish services from out-with Scotland are not benefiting the Scottish economy. After independence, they will, through money spent living and working in Scotland. Understandably the SGC are unable to estimate the benefits of this, as well as those gained by indirect taxes on goods, but they are likely to be considerable to the Scottish economy.

The SGC also cite potential rationalisation benefits to reorganising the civil service. By their calculations, the net effects of the transition would be a positive contribution to the budget. For instance, many of the senior civil service posts are based in London, where wages are on average higher. Moving the civil service to Scotland will be comparatively cheaper. Other costs will also be lower such as office space and overheads.

Conclusion

An independent Scotland would gain much more from relocating the civil service to Scotland than it would potentially lose. There are four key reasons for this;

- Firstly, the costs of this transition would be easily recouped;

- Secondly, Scotland already has the infrastructure in place to take on increased functions;

- Thirdly, whilst Scotland currently pays for the wages of civil and public servants in other parts of the UK it does not receive the benefits in terms of people actually living here;

- Fourthly, the 6,640 jobs that would be gained from relocating civil and public service roles to Scotland provide an opportunity for high skilled employment and career advancement.

It is therefore an unavoidable conclusion that the independent control over civil and public service service jobs presents a significant opportunity for Scotland.

UK state pension worst in developed world and has the highest retirement age

Extremely Good & Accurate except for the Transition Costs. If supplied by the LSE then these figures are reliable as those from the O.B.R!

The LSE did the work under contract from Scottish Government – you work with what you have and refine if you can. Scotland is data-poor.

Question.

How many Civil Servant jobs are there in Scotland that deal with work elsewhere in the UK.

I’ve just been challenged that “44,000 civil servants work in Scotland 17,000 of which work for the Scottish Government.”

the latest figures show that 42,300 people are employed as civil servants in Scotland. This is made up of 17,400 (41.1%) people working in the devolved civil service and 24,900 (58.9%) working in UK government departments.

Non-devolved UK Gov Departments include the DWP (9,300) HMRC (8,500) MOD (4,100) Department for International Development (900) Other UK Civil Service inc Scottish Office (2,100). So how is it a challenge? Is the person saying that many people work in Holyrood itself? the Sco Gov figure includes Court and Procurator Fiscal staff, Regulators like Food Saftey, Revenue Scotland the Prison Service etc and not included in those numbers would be the Police another 17,000 0fficer and 8,200 in the fire service.