Between 2007 and 2017, Southern Scotland’s regional economic wealth (GDP) measured per head averaged at only 19,599 euros. Looking at the regions across a benchmark selection of nations with similarly developed economies in northern Europe, Southern Scotland ranks among the poorest. Its regional GDP per head was almost half the average of national economies in this country selection, or roughly equivalent to the national GDP per head of the Balkan republics of Slovenia and Greece.

Seen in this light, election results in Southern Scotland seem strange. The region has returned the most conservative political results in Scotland, forging a reputation as the one consistent Scottish stronghold of the Conservative Party. In 2014, the region voted 58% against independence. Fortifying the No-vote was Dumfries and Galloway and the Scottish Borders, two of Scotland’s most pro-union areas, delivering a 66% and 67% No-vote respectively.

There is a particular irony in Southern Scotland’s support for retaining Westminster as the centre of government: the seat of power is located in a region, Inner West London, which, in 2017, was a massive 188,300 euros wealthier than Southern Scotland in per head GDP terms.

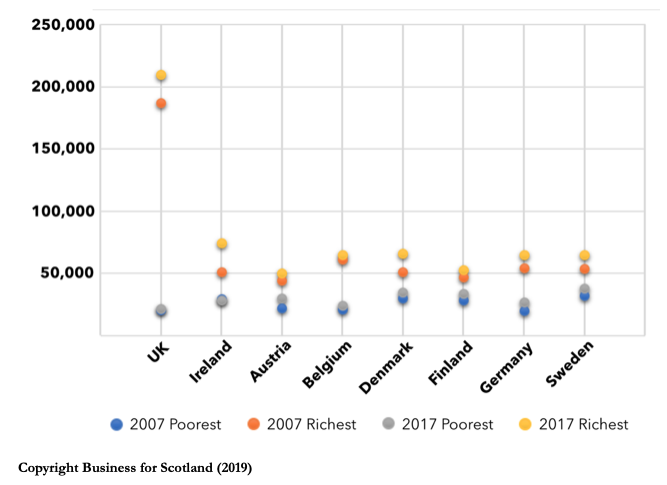

This striking inequality is the greatest visible gap in wealth between the poorest and richest regions of any wealthy state in northern Europe: the average gap was 31,088 euros. In terms of the wealth gap between the richest and poorest regions, therefore, the UK performs more unjustly than its neighbours by 157,213 euros per head.

Given the economic reality, Southern Scotland’s support for the UK can be explained using a concept called ‘system justification’: as inequality becomes more extreme, those on the negative end of it become more likely to defend the status quo. ‘This is because’, as George Monbiot phrases it, ‘people try to rationalise their disadvantage by seeking legitimate reasons for their position’.

This means that there is as much a political as economic imperative for the Scottish Government to address the situation in Southern Scotland. It is in this context that the South of Scotland Enterprise, introduced to grow the economy of this region, and due to become operational by 2020, should be placed.

Still, under the present circumstances the Scottish Government has a mountain to climb. Inequality between regions has been growing across Europe in recent times. But other states are still far from the abysmal –- and worsening — UK situation. The graph below shows the levels of inequality between the poorest and richest regions among our northern European selection and demonstrates clearly that other nations do not have the same inequality problems that the UK has created.

Whereas in 2007 Inner West London was 9 times wealthier in per capita GDP terms than Southern Scotland, this grew to 10 times in 2017. In the graph below, we can see that Southern Scotland (represented by the blue and grey dots) has seen very little growth in the past decade.

Devolved governments and local authorities across the UK still have to contend with the main thrust of the UK’s economic strategy. Since the 1970s, UK governments of both parties have pursued policies intended to make London the financial capital of the world, at the expense of the industrial base in the remainder in the country. The result has been a concentration of wealth and power in the South East, namely the City of London (a part of Inner West London), and a divergence between regions.

As a consequence of this, the overall economic situation across most regions in the UK has been tough. Looking at individual European Union regions in isolation from one another, Scotland’s 5 regions experienced, on average, a 3% decline in per head GDP from 2007 to 2017. The regions in the rest of the UK, worse still, experienced a 5% decline. The graph below demonstrates this: as a caution, what it shows is not the national GDP change from 2007 to 2017, but the average GDP change of the regions in these nations.

Looking at GDP changes from a regional level like this tells us about how growth or decline has been distributed across the state. As a whole, the national per head GDP of the UK declined by 4% during this period. But this ignores the fact that so many regions performed much more poorly than this: regions in Yorkshire and Outer London shouldered double-digit declines in GDP per head.

Mirroring this was double-digit growth in Inner West London, which experienced 12% growth while most of the country declined between 2007-2017. For sure, Southern Scotland saw a 4% increase in per capita GDP during this period (from a very low base, nonetheless), the only Scottish region to grow — it still sits, however, as one of the poorest regions among our wealthy northern European neighbours.

In contrast to this, there was a 25% rise in average per head GDP of regions in neighbouring states. Inequality, then, is not just a symptom of the poor economic performance that has dogged the UK. It is one of the central causes of it.

What all this suggests is that the most dynamic economies in Europe are proving to be those in which domestic regions are on an even level of development. History tells us that the UK is not capable of living up to this standard. Scotland’s wealth has travelled south as a distant ruling elite in London have endeavoured to maintain an economic plan that has consolidated inequality in the state.

Until Scotland breaks from the UK, its regions will continue to be throttled by the effects of the UK’s failing economic strategy. When it comes to regional inequality, voters in Scotland must understand that independence is not an extraordinary policy, but a way of aligning Scotland with the ordinary situation seen across the most developed states of northern Europe. The UK is the exception in the worst possible way.

[…] Business for Scotland Scottish independence must also aim to solve the UK’s extraordinary regional inequalities Between 2007 and 2017, Southern Scotland’s regional economic wealth (GDP) measured […]