A recurring theme among Brexiteers is that leaving the EU will unshackle UK-based firms from their Brussels-imposed chains and unleash them to do business with the rest of the world, with the UK once more regaining its preeminence as a global trading nation. (Boris Johnson’s fatuous “Let the Lion Roar” speech at the last Tory Party Conference being just the latest incarnation). Most rebuttals to this simplistic argument have tended to point out that there is nothing to stop UK-based firms doing more business globally right now, as world-class exporters, such as Germany, demonstrate. Nevertheless, a widespread assumption persists that as the UK loosens it political ties to the EU, its economic ties will follow suit. However, this assumption is blind to the fact that UK-based firms are, after all, free agents, who are at liberty to choose the particular regional and national economies (EU, UK, or both) in which they operate.

The importance of economic networks

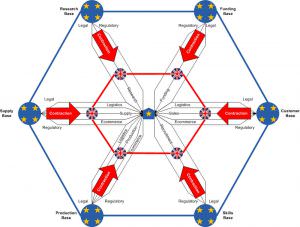

Firms do not operate in isolation, but rely on economic networks to provide them with the key resources they need to run their businesses – customers, suppliers, staff, funding, research, and production hubs. These network links are underpinned by the logistics and ecommerce channels, and legal and regulatory frameworks necessary for facilitating economic exchange.

Today, for many UK-based firms, the EU has become their most important economic network, overshadowing its national counterpart. As a result of Brexit, such firms face the prospect of their core economic network shrinking from the European to the national level. (see Image 1).

Image 1: The UK’s core economic network shrinking from the European to the national level.

Many firms will actively seek to avoid this fate by re-configuring their business operations in order to retain or strengthen their presence in the EU. This is likely to impact investment, as well as job creation and retention, and in the long run the UK’s economic capabilities.

The benefits of the EU and the impact of Brexit

The EU’s four major economic elements – Customs Union, Single Market, Schengen Area, and Euro Zone, provide firms based in member countries with a range of business benefits, which in turn support various aspects of their operating models, (for example, Sales, Purchasing, Production and Logistics). In order to retain these benefits post-Brexit, firms will need to reconfigure their operating models in line with the UK’s new relationship with the EU. This may involve changing where they are legally incorporated, where they locate certain operations, and from where they source their primary inputs, (goods, services, talent and funding). In Table 1 the business benefits associated with the four default relationship options available to the UK are summarised, together with the main business functions they underpin, (the list is indicative, rather than exhaustive). Table 2 highlights the business functions and business units potentially impacted by a change in the UK’s relationship with the EU, together with the nature of the anticipated impact – legal incorporation, relocation and sourcing. (Select the relevant relationship option to display the associated business benefits and impacts).

The tables demonstrates that any movement by the UK away from its current full EU membership can be expected to trigger significant commercial and operational changes, (involving legal incorporation, sourcing and business unit location), on the part of UK-based international firms. Opting for EFTA will allow UK-based businesses to retain access to the Single Market and the benefits of the EU’s four freedoms – the free movement of goods, services, capital and people – as well as common EU standards, and legal and regulatory frameworks.

However, EFTA means a loss of access to the Customs Union which will result in import duties, customs controls, and no longer benefiting from EU trade agreements with other countries. This, in turn, may affect where firms are legally incorporated, where they locate their sales offices, logistics and production hubs, and research centres, and may also impact from where they source their supplies and funding.

Opting for the Customs Union, on the other hand, would allow UK-based firms to retain the aforementioned business benefits, but would entail the loss of the EU’s four freedoms (the free movement of goods, services, capital and people), its common standards, and legal and regulatory frameworks. This again may affect where firms are legally incorporated, where they locate their front and back offices, logistics and production hubs, and research centres. It may also impact from where they source their funding, talent, and other inputs.

In the event that the UK opts for a Bespoke FTA, (or reverts to trading under WTO Rules), UK-based firms will forego automatic access to all the above benefits, which may, in turn, trigger wholesale commercial and operational changes across all dimensions and functions of their businesses.

Business integration and reconfiguration

Over the course of the 44 years since the UK joined the EU, international businesses based here have become deeply-integrated within the EU’s economic network. Given the momentous commercial and operational consequences of the UK’s decision to leave the EU, such firms will be proactive in taking the necessary steps to protect their businesses. The tables give a flavour of the membership benefits that firms will seek to protect, the likely business impacts of leaving the EU, and the various reconfiguration options available to international firms. The latter may involve wholesale or partial changes to legal incorporation, location and sourcing in favour of the EU, depending on firms’ specific circumstances. For example, financial services companies are primarily impacted from a legal and regulatory perspective, (including so-called ‘passporting’ rights), and have proved to be early-movers in terms of reincorporation and relocation to other EU countries. All such solutions are likely to prove costly for firms, given the necessity of repositioning or fragmenting their business models. Large corporates with deep pockets will find it easier to transition than smaller businesses. Some sectors, such as motor manufacturing, will require longer timescales in which to reconfigure themselves, hence demands for a long ‘transition period’.

The economic consequences of Brexit

For the UK as a whole, however, Brexit will remain the economic equivalent of ‘walking the plank’. (Even the Government’s attempt to extend the length of the plank by buying itself a two-year transition period fails to meet the expected span of a five-year-plus trade negotiation). Consequently, despite some anticipated business reconfiguration in favour of the UK, the EU’s relative size (ten times that of the UK) means that the overall impact of Brexit is likely to be overwhelmingly negative. This can be expected to have a profound economic effect on local communities, regional economies and the UK Exchequer. The immediate aftershocks are expected to be felt through lost jobs and investment, and lower tax receipts, resulting in a knock-on effect on public finances and services. In the longer term, the UK may see a significant erosion of its competency and skills base, especially in vital high-tech sectors, which tend to rely on large and diverse economic networks in order to provide a deep pool of knowledge and know-how. And if political attempts to distance the UK from the EU only serve to deepen many UK firms’ degree of European integration, it will be one of the supreme ironies of Brexit.

This is an opinion piece by guest writer Greg Elliott.